| |

|

| |

| |

|

Once

upon a time there were some pieces of wood... Paraphrasing

Carlo Collodi you maight start in such a way the story

of a violin making but also of a viola rather than

a cello. In a certain sense, a reference to the fairytale

of Pinocchio can be fitting if you think about the

final result deriving from working the raw wood when

the able hands of the craftsman put his just completed

work into the same expert hands of a musician. A real

magic seems to be happened.

The concerned pieces of wood

are not ordinary pieces of wood. Their names sound

like titles:

"Spruce from Val di

Fiemme"

"Balkan Mountainous

Maple"

"Black Ebony from Madagascar"

That's quite enough to get

impressed facing such a blazon!

|

|

|

|

|

|

Actually, the black ebony

from Madagascar would be really the best for a luthier.

But, on the other hand, it is not easy to get it,

so the most common ebony from Africa is really the

most used.

Now,

let's have a brief look on how a violin, the symbol

of the string instruments by definition, is made according

to the canons of classical violin making. The pictures

below may help to do that by highlighting the main

components of the instrument.

|

|

First

of all we should watch two components in particular:

those ones having not so obvious a specific functionality

unlike the others. These components are the "bass

bar" and the "sound post".

|

| The

bass bar is a strip of fir wood appropriately shaped

placed under the soundboard parallel to the strings

in correspondence of the thicker low tone ones (third

and fourth). These ones, through the left foot of the

bridge, exert a considerable force on the board itself

and so the most evident function is that of a reinforcement

of the structure. Moreover, it also spreads low tone

string’s vibrations across the soundboard. |

|

| In a similar way the sound

post, a small fir cylinder interlocking between the

soundboard and the back and symmetrically positioned

to the bass bar near the right foot of the bridge, performs

two functions: the main one is acoustic since it transmits

vibrations from the soundboard to the back of the instrument

allowing the resonance of the whole sound box; the other

function, like for the bass bar, is spreading the force

exerted on the soundboard by the strings unloading it

to the back. |

|

|

The acoustic success or failure of the whole instrument

may depend on a more or less positioning of these

components by the luthier to confirm that very often

what you can't see is what makes the difference. It

means mastery of technique acquired after years of

intense learning and enthusiastic experimentation.

|

|

Marco Cioni who, since

he was a teenager, called himself "aggeggione",

a Tuscan term identifying a person who knows no statements

such as "I cannot", "I am not able"

because he tries and tries until he succeeds, found

many writings by ancient master luthiers around the

world, such as Domenico Angeloni, Simone F. Sacconi,

Antoine Vidal and, judging by the results, he studied

them very carefully.

He says: "To make my first violins I followed

the directions stated in the book "The Secrets

of Stradivari" by S. Sacconi. As a first result

I got a too small violin of 34 cm and a half. The

second one turned out to be too large, just over 36

cm".

Well, things happen you would say.... if you think

that the standard size is 35.6 cm ...!

Now, after more than ten years of learning and experience,

Marco makes string instruments by manufacturing one

by one all the necessary parts and using woods of

the classical tradition but not only.

"A string quartet (typical set of a luthier's

manufacture which consists in a viola, a cello and

two violins) should be get from wood taken from the

same plant", explains Marco. "Usually I

employ traditional wood but sometimes I like to experiment".

And he continues: "To make the linings, for instance,

I use a timber that spontaneously grows in Torbecchia

(the place where he lives). My uncle, a carpenter,

used to call it Salia but it is a type of willow,

actually. Even Stradivari sometimes used the willow",

he smugly says. Marco continues: "Even here,

around the house, it grows another type of plant that

surprisingly revealed unexpected acoustic qualities:

the Robinia or Locust-tree. I have a client, a friend

of mine as well, who is a concertmaster of the Sanremo

Symphonic Orchestra", he says with a touch of

pride, "that honored me by testing my instruments.

He really likes this wood, as he has pointed out more

than once.

One of the first times I used that wood, I remember

I had prepared a tailpiece made with Robinia and sent

it to him by mail without any particular expectation,

actually. Well, he phoned me, surprised by the peculiar

characterization of the sound achieved using that

tailpiece". A great satisfaction, let's face

it!

|

|

|

| |

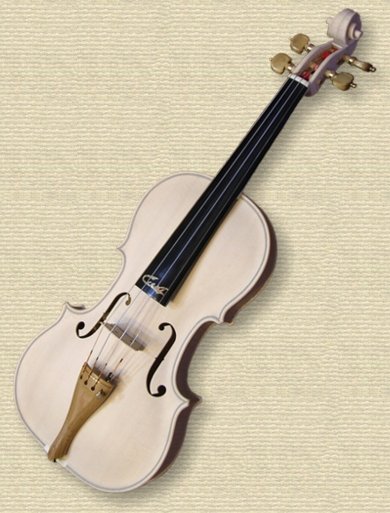

Here

is one of Marco's instruments made with some no traditional

wooden components. It is a violin, a part of a string

quartet. The chinrest is made with Robinia; tailpin,

tailpiece and pegs are made with Erica, another kind

of wood revealing interesting acoustic qualities.

Another particular feature concerns the upper nut. In

this case wood is not used (usually ebony is used as

well as for the lower nut). In fact it is obtained by

an ox bone which is previously treated with sodium hydroxide

(caustic soda) and boiling water. It is not so unusual

to find some instruments from Marco's manufacture showing

both upper and lower nuts made of this material. Some

examples of this are given by the violins displayed

further on in this section.

Furthermore note also the gold trim on the pegs and

the inlay on the fingerboard made of gold as well and

showing the Author's brand name. |

|

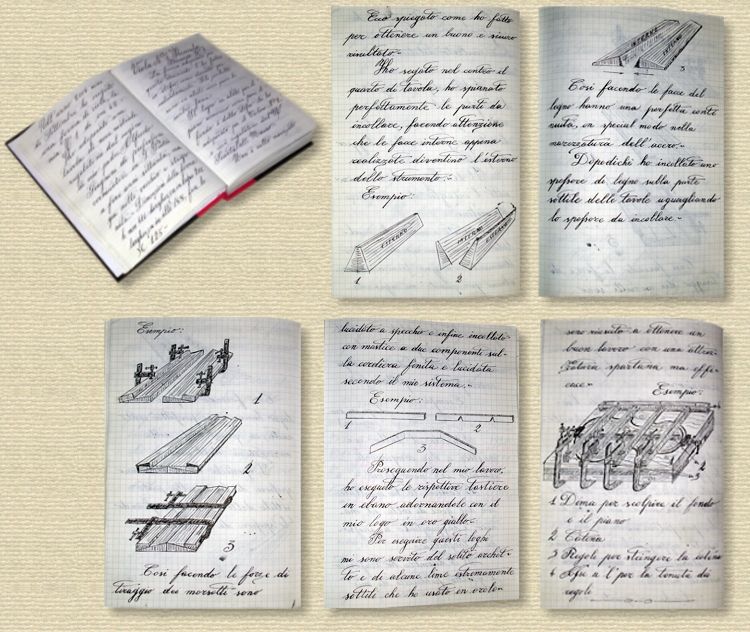

From

the beginning of his apprenticeship Marco kept a diary

of his own experiences like an explorer in distant lands

that minutely updates his travel notebook at every rest.

With the patience of an amanuensis monk, Marco wrote

down everything in great detail and accurate pictures,

everything in a calligraphy as they used in the past.

|

|

| Marco

slowly does all this just for pure passion, in the quiet

of his laboratory. Free of constraint and deadlines

of any kind he does not use semi-finished parts but,

as already mentioned, he makes his own everything he

needs. |

|

To complete the real violin making manufacturing

process, that is, bringing the violin into a state

called "in pajamas", as the jargon has it,

- which means unpainted - , it may takes until a month.

The adjoining photo shows just a "still-to-be-dressed-up"

violin, a procedure that, we must not forget, may

take even a longer time.

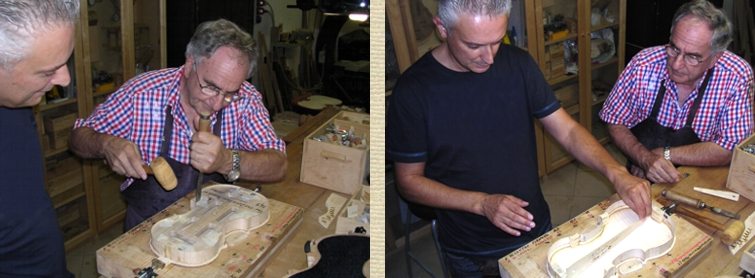

Note that Marco spends part of his time also to convey

his art to other people. It is not so unusual, if

you come to his lab, to find him chiseling a soundboard

and, at the same time, keeping up with one or more

apprentices who get the teachings of the master.

It is Marco that tirelessly strives to show them the

various techniques, wood modelling, natural glue preparation,component

assembling and finishing operations.

In the pictures on the side and below we can see Marco

teaching Alessandro how to remove the internal shape

on which ribs and linings have been assembled after

they have been glued to the back of the violin.

Afterwards, the squareness of the blocks to the horizontal

plane is checked.

|

|

|

| At

the end of this section let's get back for a while to

the Robinia wood so that we can speak about a sort of

"experiment" that Marco successfully completed

some time ago and that made him assume, at that time,

the role of heretic - metaphorically speaking - against

the orthodoxy of violin making. |

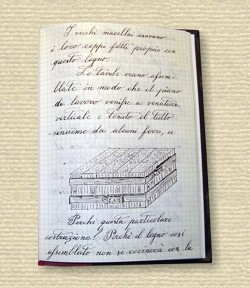

| As mentioned above, Marco

gets the Robinia wood around his house. Many years ago,

a significant number of cut down plants were abandoned

on the ground. He says: "There were several huge

nearly century-old trees torn down and left in the woods.

They had never been cut to make firewood. About ten

years ago I collected those trunks which, in the meantime,

had lost bark and sapwood, devoured by termites and

elements. I had some of those logs sawed to tables”,

continues Marco, "to make a cutting board".

For more information about the peculiarity of this cutting

board, click on the image at right to directly read

from Marco's notebook. |

|

|

After

discovering again this "essence", - like a

tree species and the wood you can get are defined within

forestry -, Marco began manufacturing some tailpieces

made of Robinia with excellent results. Among them,

regarding one in particular, we have already talked

about. It was a really short step from there to find

himself wondering why not to manufacture a violin that

were almost completely made in Robinia. Said and done! |

|

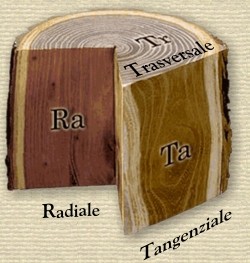

From

one of the best preserved logs, with a tangential cut

from the trunk area known as "heartwood" but

however as close as possible to the rind or bark, Marco

got the necessary pieces for the back, ribs and neck

of the violin. Even the tailpiece, chinrest and pegs

were made using the Robinia but, like the different

color of them suggests, they were got from a different

log. On the other hand, Marco used some willow wood

for linings and blocks. Finally he used, with a certain

relief for purists, the classic spruce wood for the

soundboard, sound post and bass bar.

The result is the instrument you can see in the pictures

below. Those who tested it say that you only need to

lightly touch the strings to realize that this violin

has an excellent music performance.

Congratulations, Marco! |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|